THE STORY OF THE LOST TBM

Pilot’s Testimony of Grumman TBM Avenger

Pilot’s Testimony of Grumman TBM Avenger

N337VT Crash at the White River Reservation

Mountain Range in Fort Apache County, Arizona

November 26 UPDATE, scroll to the Botton for LiDAR search area map. Most probable crash location within this zone.

We all need to try and find this airplane for our American heritage.

Crash date: May 6, 2018 (Narrative: May 15, 2018)

We all need to try and find this airplane for our American heritage.

Crash date: May 6, 2018 (Narrative: May 15, 2018)

Written by: Ron Carlson - Owner & Pilot

Parachute Drop Location:

Approximately 20 to 25 miles east of White River Indian

Reservation, Airport (E24)

LATES UPDATES:

A tale of survival and the search for a lost plane

FROM THE WHITE MOUNTAIN INDEPENDENT NEWSPAPER IN SHO LOW AZ

Tribe warns of closures to those seeking missing airplane

The Story

THE AIRPLANE - 1945 GRUMMAN TBM AVENGER 3E - N337VT

A tale of survival and the search for a lost plane

FROM THE WHITE MOUNTAIN INDEPENDENT NEWSPAPER IN SHO LOW AZ

Tribe warns of closures to those seeking missing airplane

FROM THE WHITE MOUNTAIN INDEPENDENT NEWSPAPER IN SHO LOW AZ

The Story

THE AIRPLANE - 1945 GRUMMAN TBM AVENGER 3E - N337VT

The Grumman TBM Avenger is a Navy war plane that was used extensively in the Pacific theater during World War 2. It was primarily based on and operated off the fleet aircraft carriers.

The TBM has positions for 3 crew members: Pilot, Rear turret-gunner and Radioman/bombardier.

The rear facing turret was equipped with a .50 caliber machine gun in an electrically driven all-axis rotating ball, in which the gunner is totally encased. The armament platform also includes two forward facing .50 caliber machine guns, one in each wing, along with a 2,000 pound Mark 13 torpedo in the bomb bay. Later in WW2, standard operations pivoted more to utilizing other payload options within the bomb bay, which included multiple bomb size and quantity configurations. Even later, further implementations included mine laying, depth charges and other conventional and unconventional arms and tactics. The TBM was versatile. Radar allowed the TBM to operate at night, one of the first carrier planes to do so for seeking the nocturnal enemy bombers.

The TBM has positions for 3 crew members: Pilot, Rear turret-gunner and Radioman/bombardier.

The rear facing turret was equipped with a .50 caliber machine gun in an electrically driven all-axis rotating ball, in which the gunner is totally encased. The armament platform also includes two forward facing .50 caliber machine guns, one in each wing, along with a 2,000 pound Mark 13 torpedo in the bomb bay. Later in WW2, standard operations pivoted more to utilizing other payload options within the bomb bay, which included multiple bomb size and quantity configurations. Even later, further implementations included mine laying, depth charges and other conventional and unconventional arms and tactics. The TBM was versatile. Radar allowed the TBM to operate at night, one of the first carrier planes to do so for seeking the nocturnal enemy bombers.

The TBM has 3 fuel tanks. Each wing contains one tank at 90 US gallons, located near the fuselage at the wing root. In addition, there is one center tank that holds 145 gallons. Total fuel equals 325 gallons. Total endurance range is approximately 3.5 hours, depending on power settings and altitude factors. Fuel required is 100 low-lead octane fuel. The burn rate is approximately 130 gallons per hour during take off, 100 gallons per hour during climb, and 70 to 80 gallons per hour during cruise.

The engine is a Curtis Wright 2600–20 Cyclone engine. 1900 horsepower. There are two rows of seven cylinders each. This engine is designed to burn approximately 1 gallon of W120 weight oil per hour. Sometimes, depending on engine tuning and/or power settings, the engine burns a higher rate of oil. The oil tank holds 32 gallons.

2018 WORK ON THE AIRPLANE AND PREVIOUS FLYING

I had purchased the Grumman TBM Avenger N337VT in early 2017. The TBM was delivered via cargo ship from Brisbane, Australia to the docks of Long Beach California in the fall of 2017. After US Customs was approved, the TBM was delivered by truck to Long Beach Airport (KLGB). There it was completely serviced and then a ferry permit was granted by the local FSDO for me to fly the TBM to Stockton California (KSCK). I then flew the TBM to KSCK. There it was to receive all the service and maintenance it would require, and also received some additional cosmetic work. Then I would fly it back to Chicago in Spring 2018.

While at Stockton airport, the TBM was re-certified into the LIMITED category (no night flights, no IFR). In addition the TBM received the required maintenance, the 2018 “ANNUAL”, re-registration to the United States, and re-certification in the “LIMITED” category. This was done at Vintage Aircraft at Stockton Airport (KSCK). After the required maintenance and required paperwork was completed, I flew the plane in the vicinity there. Further cosmetic work was executed to the TBM, which included propane/oxygen simulated forward firing wing machine guns, work to the rear machine gun turret and very extensive work to the radio room, with a large quantity of vintage radio and control equipment added.

I finally departed Stockton on Wednesday, May 2 with the destination of Torrence Airport, but was unable to make Torrance because of weather with low ceilings moving rapidly into the overall LA area. So I diverted and landed at Bakersfield Municipal Airport (L45) and stayed overnight there.

The next morning, on Thursday, May 3, I departed (L45) and flew to Torrance Airport (KTOA). The TBM remained parked at Torrance Airport until Sunday, May 6, 2018.

JUST BEFORE THE VOYAGE FROM CALIFORNIA TO ILLINOIS

On the morning of Sunday, May 6, 2018, an overall flight-plan was reviewed by Ken and myself at breakfast. Ken is my friend, also a pilot. He was to accompany me on the journey home and fly in the middle seat. The plan consisted of seeing up multiple flight legs, starting with a departure from the LA area of California and ending in the Chicago Illinois area. We were taking a “southern route”.

On the first leg of the flight plan (Torrance to AK-CHIN) I checked the oil at 26 gallons. I had added 3 gallons while at Torrance Airport. We departed with full fuel and 29 gallons of oil, more than enough for one of each, a 2 hour leg. No flight was planned much more than 2 hours, so easy to add oil if needed in order to keep the tank topped off.

On Sunday, May 6, 2018 at approximately 9:30AM, we planned to depart Torrance Airport. Prior to departure, I gave Ken a full walk around of the airplane and performed the written preflight checklist together. He was to become a crew mate. In addition, I gave Ken a full briefing of where the emergency gear was located (the stowage tunnel behind the middle seat location, where a life raft was typically located on the original Grumman design) and how to access and remove it.

The emergency gear included one month’s supply of energy food bars for two, 48 bottles of water at 16 ounces each, one fully charged satellite phone with active Sim card, with fully charged second battery spare, one portable ELT (ACR 2881 ResQLink+ PLB Floating Personal Locator Beacon), which was fully serviced with new battery two weeks before.

In addition there was a large survival gear bag that was packed extensively, which included (but not limited to) two small plastic pup tents, emergency blankets, water purification, fire starting matches, fire sustaining fuel bricks, medicine and bandages, knives, compass, signal mirror, strobe lights,

flashlight, snake bite kit, and all the other typical survival necessities.

|

| Ron at Torrance Airport just before departure. |

Then I oriented Ken with the middle seat, which he was to occupy. I explained how the canopy opened and closed and where the red release knob was located in case he would need to bail out, in order to jettison the “greenhouse glass” canopy. I also pointed out the communication systems, the navigation systems, and multi-point restraint harness located in the seat.

I then further discussed in detail how the parachute worked; how to get in it, where the straps were to tighten it if a jump was imminent. I had told Ken to watch certain related videos from the parachute manufacturer prior to the trip, which he did watch. I also explained about the techniques to exit the airplane, especially to make sure to duck and dive low off the wing before letting go in order to minimize the risk of being hit by the tail of the airplane.

Then I had Ken sit in the seat, strap on the parachute, strap on the multi-point harness. Once Ken was situated this way, I had Ken go through a partial process of a mock emergency by having him quickly pull all straps tight to simulate an actual emergency.

VOYAGE FROM CALIFORNIA TO ILLINOIS

On the first leg of the voyage, I planned to land at an airport near Phoenix, south of Phoenix. I chose (A39) AK-CHIN based on good fuel pricing. (This information is all shown real-time on Foreflight navigation database which is updated constantly).

The initial attempted landing at (A39) was not smooth and not with full runway centerline directional management, so I aborted the landing early with a go-around. The second landing was smooth and successful. Refueling and checking the oil took place. No oil was added or required to be added, but the fuel tanks were all topped off full. Taxi out and normal run up did not yield anything out of the normal. (Note - It was very hot, approximately 90 degrees or higher on the ground. It was more difficult to start the engine than normally).

The TBM climbed normally, at 800 to 1000 ft./m. I climbed to approximately 11,500 feet, which is a normal east-bound VFR flying altitude level for that

direction of flight. An approaching north/south continuous mountain range had to be crossed. The lowest initial altitude on the continuous ridge line rose from 8 to 9000 feet MSL. The plan was for us to stay as high as reasonably possible - to cross over at 11,500 to 12,000 MSL for:

(1) Safety of highest safe altitude (no oxygen on board).

(2) Maximizing ground speed based on tail winds.

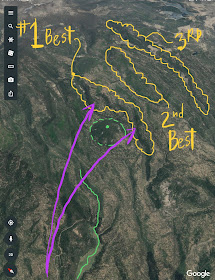

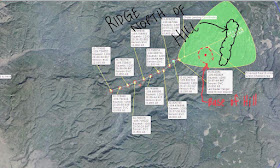

My plan for this particular leg was to fly a slightly winding route that would pass near the following airports in succession, in this order off the main direct flight path to Albuquerque, New Mexico:

Fly just north of (P13) San Carlos Apache Airport,

Then

Fly just south of (E24) White River Airport.

Then aim to angle south of the direct route to KAEG to avoid the highest mountain terrain - towards just north west of (13Q) Jewett Mesa Airport.

Then on to the initial final leg destination - (KAEG) Albuquerque Airport.

Based on in-flight calculations, there was a yield of favorable tailwinds, and with the normal fuel consumption, I changed the destination from (KAEG) to an airport a bit more distant - Las Vegas Municipal Airport (KLVS).

THE ENGINE GOES

The TBM was flying level at 12,000 feet crossing the beginning of the most mountainous part of the entire voyage from LA to Chicago, with the highest ridge that we would have to cross. My plan was to slightly deviate from the direct route to (KAEG) all along the way as required to cross over terrain no higher than 8000 to 9000 MSL. I was starting to angle more southerly towards a position 10 miles northwest west of Jewett (13Q) when there was a large bang that came from the front of the TBM. The first two things that I perceived immediately was very heavy gray smoke emanating from the top and top-sides of the engine cowling - and a very violent shaking from the entire front of the TBM. Both all at once.

The smoke was coming out the top and side airflow ports at the rear of the engine cowling. I had then presumed obviously that there was a major engine mechanical problem. Airspeed indicator showed that our speed was already dropping rapidly, and the TBM was already slightly descending, which signified that the engine was not producing very much thrust anymore at cruise power. I then pulled back the throttle in an effort to reduce the fire and smoke.

(I did not initially observe any fire, but Ken did from his vantage point). After reducing power, there seemed to be no reduction in smoke. I could see slightly in front of me. No smoke in the cockpit, just in the entire air-stream surrounding the cockpit.

Then I logically brought down the nose slightly to maintain airspeed. I simultaneously looked out and down again to left and right for landing locations. I was always looking, and at this stage I was on red alert because there seemed nowhere even near clear to land for the last 10 minutes. The airplane had now dropped to probably approximately at (or just above) 2500 feet AGL and still descending. The ridge line we were over was approximately 9000 MSL.

(I have looked back and pinpointed the location and checked the actual elevation).

There was only one possible off field landing location - on the starboard side. But this terrain looked questionable, looking through the smoke coming from the front. From 15 years of bushpilot experience in Canada and the High Arctic, I know a little about judging terrain. This is critical for seaplane and tundra tire landings. I had previously made 2 successful dead-stick landings, one of which was on floats onto tundra, with no damage to airplane either time. But with the presence of water and muck, gear up with low wings, high airspeed and no room for error for an undershoot or overshoot, this seemed like a 50/50 at best to not end up in a situation with the plane cartwheeling, flipping over, or running out of room and barreling into the big pine trees, or worse.

The open terrain looked like a marsh with water in the center, surrounded by large trees. Significant water this time of year in spring. The marsh seemed long enough to execute a wheels up landing, but being unsure of the context of the terrain (water, muck, mud or worse, and - was it flat or did it slope down with the mountain?) and with thicker and thicker smoke coming from the engine area, forward visibility was already very much in question. The smoke was increasing. My initial thought was “what if the smoke got worse to where forward visibility was zero?” The airplane was now probably between 1500 and 2000 feet AGL (10500 and 11000 MSL), and still descending. There seemed to be no thrust, of course the engine was running, it did not quit. Still time to bail. Not at the point of no return. Many questions in so few seconds.

So with the two factors of questionable terrain and worsening forward visibility, and coupled with Ken’s willingness to jump (Ken voiced this unsolicited on the intercom), I made a final decision to abandon the TBM in the air.

(Note: Ken later testified that there were sheets of oil spilling out the right side. Not a continuous flow, but continuous interval of sheets of oil).

BAIL OUT

Intercom intelligibility was sporadic. Maybe it was the increased background noise. I could hear the landing gear warning horn blasting. (We could barely understand each other in normal flight, inherent with this airplane and configuration). I hand signaled back to Ken to bail out. In seconds Ken was out and gone.

At this time the TBM was down to probably about 1200 to 1500 feet AGL (10,500 MSL).

(Note: I was unaware that, although Ken did exit the middle seat position from the airplane, he in fact climbed down hand over foot and kneeled on top of the wing, but did not jump off. In later testimony, Ken said that he grabbed the recessed hand grip on the side of the fuselage and, while then laying on his back , he rode on the wing root on his back, while his legs were hanging over where the split flaps are located, into thin air. It was only until I banked the TBM in the right turn, that Ken finally let go and fell, just missing the tail coming over above him).

Smoke was getting pretty thick now. I could not see forward very much at all. On instruments, I pulled the nose up 20 or 30 degrees and turned the TBM into a climbing 60 or 70° turn to the right. As I was doing this I thought to myself: “ Are we really going to do this?” That didn’t cause hesitation, I knew I was committed and going to do it. But I did say it to myself. It was like I couldn’t believe what was happening, and what was going to happen.

I then bailed out, also lucky in successfully avoiding being hit by the tail. I believe that a possible reason is because I had the airplane trimmed for level flight before entering the climbing turn and when I let go of the stick, the tail came up and the nose came down, in the ship’s attempt trying to return to a normal attitude on its own (as Kenny confirmed from his vantage point floating down in his parachute). I was going down as the tail was going up. That may have helped. But that is conjecture.

Bail out altitude was somewhere at or below 1000 AGL. (This has now been confirmed by radar returns of our transponder squawking 1200 from Denver ATC recordings). 100 to 150 foot high Ponderosa pine trees awaited below. (Update - later calculations put me actually at 800 feet AGL when I exited the aircraft).

If going down in the wrong position, G forces can definitely work against you, trying to hold you in. With our TBM situation, I had to deal with that in a different way - I avoided the G forces by pulling the plane up and turning it hard right. I wanted to be more in (or as close to) a zero G situation if possible. I always had planned to go upside down, but I was very low. That had me worried. I had thought way ahead of time what I would do and I executed that maneuver. Because I was low, I didn’t want to go upside down (like a lot of the World War II pilots, especially Luftwaffe pilots) because then the plane probably nosedives. You are definitely committed to getting out fast. All or nothing at that moment. I was thinking about what if I got snagged trying to get out? Just one possible problem of many I suppose. Never have bailed before. Instinct. You just act —there’s no time to think.

I was fully aware and lucid during every second of bailing out. I remember every microsecond. I recall vividly growling out loud and a surge of adrenaline pumping, helping me get out of the cockpit. I remember that it was very hard to pull myself out, even though when I had the plane in the climbing turn making me feel somewhat weightless in my seat. The slipstream was strong. It was more the slipstream that was holding me (against the rear part of the side canopy).

Looking back, it definitely takes some strength and determination to get out - probably in most situations. I don’t know how Ken had held on once he got out. He indicated later that it’s just adrenaline and you’re using all your strength and not even thinking. I remember getting a little bit hung up from the slipstream onto the side canopy behind me halfway out, but it was very quick. My legs of course came out out last, and once breaking free, I instinctively put myself in a cannonball position and closed my eyes, waiting for the elevator or rudder to smash me in the back. After about one second, I opened my eyes and I was looking straight up at the sky in the most surreal and peaceful free-fall.

The first thing I perceived as I was free falling was the blurred shadow of the TBM tail disappearing to my left. Of course my right hand was already grasping for the silver D ring to the ripcord. As I pulled, I did also use my left hand to push, as I had learned from reading and the videos. I knew I was low and I had to get this thing pulled as fast as possible. I was in the wrong position facing up, falling on my back. I didn’t think I had time to put my arms out and try some rollover maneuver. I have never parachuted before. I didn’t know where the ground was, but I assumed it was close. It was probably lucky that I didn’t know enough to try to turn over because that would have wasted another second or two which could have been the difference in not having enough time for deployment and slowing down before hitting the trees.

After I pulled the D ring, I did clearly observe the small pilot chute deploying, then the telltale violent shock of the main chute opening. It felt as if I hitting a brick wall. A massive huge shock to the body, but a calming and relieved feeling. It did take my breath away. In that first instant I was dazed. I was already coming down near the top of trees, and they were coming up fast. I had just a few seconds it seemed to look to my right and I saw Ken floating down successfully in his parachute, almost the same level, a bit higher, a quarter or half mile away. That was a big relief. He was close to me considering that we were in two completely separate bail outs. I last looked to my left for the TBM, but saw no sign of it.

(Note: We dropped close together because, as stated earlier, Ken had stayed with the TBM until I started the hard climbing turn, which was just a few seconds before I bailed out. Ken later testified that he watched my parachute open, and then saw the TBM eerily start to level itself back out, in it’s decent, remaining in a somewhat gentle turn).

I was then just above the tree top level and coming in fast, so I crouched in a landing position with my knees bent just before hitting the green canopy. At first, as I crashed through the branches, the treetops seemed to slow my descent, but then the parachute apparently collapsed. It seemed I then went into a free-fall for the last 20 feet or so. I did not have my goggles pulled down, but luckily most of my face was uninjured while hurtling down through all the branches.

I remember hitting the ground very hard on my legs and back, a bouncing feeling off the earth, rolling backwards and then hitting the back of my head extremely hard on the ground. I was wearing a premium WW2 replica vintage kevlar helmet and this must have saved my head. I was dazed at first, but solidly on the ground. The first thing that I perceived was that I was coughing some blood out of my mouth, with a pretty good nose bleed at the same time, probably from the overall concussion. This stopped almost immediately. After a few more seconds I started to unbuckle myself from the harness.

I tried to assess my injuries as best I could. I was not in that much pain - yet. (in parentheses - x rays and prognosis from hospital):

(1) Sprained or fractured left ankle (severe ankle sprain). Right ankle less of a sprain.

(2) Chest hurt (broken rib).

(3) Back hurt (strained).

(4) Neck hurt (strained).

(5) Nose bleeding.

(6) Right elbow hurt (strained).

(7) Cuts and contusions (multiple on face and body).

(8) My right knee injury was more apparent much later.

(8) My right knee injury was more apparent much later.

(Note: Ken landed at about the same time and was stuck 20 to 30 feet up in a tree for several minutes. The tree that he was in had no branches, it’s almost like a telephone pole. There was no way to get down. Reaching for another tree that did have significant branches which was leaning close by, he transferred himself and disengaged from his parachute harness. That tree gave way and Ken fell while hanging on all the way to the ground below. Ken sustained a major facial injury to the left side, with a heavily bruised eye and cheek, with broken cheekbone. Ken also sustained a bruised or fractured wrist).

|

| View looking down from Ken's position stuck up in the tree. |

|

| Ken's parachute where it was stuck 20 to 30 feet up the tree |

SEPARATED IN WILDERNESS / SEARCH TO FIND HELP

I then assessed what I had within my possession. Apart from the parachute and helmet, I had on my pilot flight suit, my shoes stayed on, and only my cell phone and wallet. My small notebook pad was laying 10 feet away with the broken Velcro leg wrap, but the pen was missing. In retrospect, it would’ve been easy to put a cigarette lighter, knife and a small flashlight in my breast pocket. Further insight would’ve been to take the satellite phone and/or the portable ELT that I had placed in the TBM emergency life-raft tunnel, and instead zipped those into my leggings. Maybe even add in a bottle of water for good measure. But future pilots can take this advice to better use.

I hiked in the approximate direction from where I thought I had last seen Ken when he was in his parachute descent. I spent about an hour calling and searching for him, without success. I returned to the location of my parachute. I tried to pull my parachute out of the tree but I was unsuccessful. This could have been a good tool for SOS and also use as a blanket at night. This is where a good large knife would have helped.

I started to hike parallel to the mountain and after a short distance, there was a small clearing in the trees. At the other edge of the clearing crossed an old logging trail. The trail was heading up and down the mountain. I hiked up the mountain ridge trail and followed it for 2 hours to its end in order to try to get a cellphone signal. Before embarking on the hike, I had placed white notebook paper on flat rock with a stone on top in the middle of the trail. I also put white paper in a small pine tree sapling next to the trail. Further, I drew arrows in sand at certain points, in several locations, showing my direction of travel on logging trail. Maybe Ken or someone else might find it.

I hiked to the top of the mountain ridge and got one bar signal on cellphone, but no matter what, I could not get any texts or voice calls out effectively. Left ankle was now swelling up, painful. Right ankle sore. Now I was hobbling / shuffling.

At that point I was getting very dehydrated, had to find water or any other hydration source. Mouth completely dry. My back was starting to cramp up. I started the march back down the mountain ridge, back to original drop location. On the way, I was able to chase down, trap and successfully consumed (mostly just the outer part) of a small frog type looking lizard for food source. (I later learned from a friend that lizards typically carry salmonella. So I wouldn’t recommend that in the future).

I then made it back to where I had originally landed. I searched and called for Ken a little more, but then figured he was either unconscious or worse. So my first thought was that I really needed to find search and rescue people ASAP to help to find Ken. With growing ankle pains, especially the left ankle, hobbling, back cramping, I now couldn’t walk too far without long rests. I was thinking if I could find help, I could at least guide the search effort to get to Ken. I wasn’t going to be able to do it myself now.

The primary mission now was to find water. Not only was my upper back really starting to cramp up, but also my thighs a bit. In the afternoon that day was in the 80s and very dry. Air significantly thinner to breath at 9,000 feet. If I could get down the mountain, there seemed decent odds to find a stream. Unfortunately for me, I normally get dehydrated rapidly, so I knew this was the most important thing.

I hiked down a couple of more miles down the trail. I saw no other footprints. Not a good sign for what might have happened to Ken. It started to get dark, so I needed to make as best of a bedding location as possible, figuring that the temperatures that high up in the mountains would get very low at night. In the meantime, I was starting to cramp up even more from dehydration.

Just an hour or two before dark, I stopped hiking and off the trail I found a small stand of young pine trees. I made a pine-needles bed and pine-needles pillow, and in addition broke down a number of pine-bough branches to use as a makeshift blanket covering and semi-shelter, all for protective insulation. I had made a low ridge pole from a dead tree, and built up the pine on both sides the length of my body.

It was a long night. The temperature must have dropped to the 40’s. The pine needles and boughs definitely took the edge off, but there was little sleep for me. The mosquitoes kept trying to get under the pine bough layers. The mini-shelter really worked great, the pine needles prevented them penetrating. However, I couldn’t really lay still for any position for more than 15 minutes because of (what I found out later to be) a broken rib and back and neck strains. I then drank my own urine at around midnight (in survival study, you can do that one cycle effectively) so as bad as that tasted, that that helped bring the cramping down to get through the cold night ahead, and subsequent further marching.

It was a long night. The temperature must have dropped to the 40’s. The pine needles and boughs definitely took the edge off, but there was little sleep for me. The mosquitoes kept trying to get under the pine bough layers. The mini-shelter really worked great, the pine needles prevented them penetrating. However, I couldn’t really lay still for any position for more than 15 minutes because of (what I found out later to be) a broken rib and back and neck strains. I then drank my own urine at around midnight (in survival study, you can do that one cycle effectively) so as bad as that tasted, that that helped bring the cramping down to get through the cold night ahead, and subsequent further marching.

|

| This is the shelter that Ken constructed for overnight. |

I knew there were probably wolves, coyotes and bears, but I wasn’t really too bothered with that. A vulture was circling me earlier during my hike back down the mountain, but I gave him a few good waves, so he probably thought I was a hiker and moved on. You don’t want a vulture circling you - that is like sending up a smoke signal for predators. I was thinking more about the possibility of there being a healthy mountain lion population (later confirmed). At one point in the night I heard something large move by. It could have been an elk...who knows. I kept very still and quiet the entire time as best I could. It certainly couldn't have been a mountain lion. That’s all I cared about. You probably wouldn’t ever hear one of them come in before it was too late. Not a good move to not even have a knife in my possession. I had always believed that a good knife is your number one survival aide, always first on my list.

At 2 or 3AM, the moon came up and I decided to get up and start walking down the mountain again, using the moonlight. I badly needed to find water. Often stopping in the dark to look around and listen, I finally stopped and heard what sounded like water. It sounded like a small babbling brook or something. I thought I was hallucinating, I sure didn't believe it. It was to the left side of the trail down the mountain. So I finally convinced myself to walk off the trail - I remember, and then I slid on my back down the mountain side, over rocks, logs and other things - to get closer to the sound.

Amazingly I then stumbled upon a big gravel road. That was a great sign of hope. Not only possible water - but a real road. I went across the road, then lower and down by what must have been a small creek...and then feeling my way in the dark to the sound of the water, I did finally find it. I laid down and drank as much of this ice cold water as possible. Now I knew the odds were much better in favor of getting out. A person can last for many many days without food, but not without water.

Still very cold I then had to pick and construct another bedding location. This one was not nearly as good. I could not stop shivering. I stayed there by the creek for another 4 hours until the sun was starting to hit parts of the road. I then hobbled up the road to where the sun was. I sat basking in the sun to try and warm my body up. That started to work.

REUNITED

Within 5 minutes of sitting in the sun, Ken came crashing down the same hill and popped out onto the road. He said he saw the signs on the trail (the arrows and papers). He found the same trail and also knew best to come down the mountain. Biggest relief. Both of us alive and relatively well. Ken’s main injuries included a very banged up left side of his face, and sprained or fractured wrist.

We both decided to take the road and go a certain distance up the mountain. After going a small distance up the road, a decision was made to reverse course and go the other way, which was leading down the mountain. What we didn’t know was that this gravel road lead some 25 miles down the mountain finally to a paved road, which would lead to a nearest town called White River (Indian Reservation).

I was hobbling pretty slow at this point, and suggested to Ken to go ahead a few miles. If he didn’t find anything, to come back. That under any circumstances, we must not be separated. 2:00 PM was to be his turnaround time with 4 PM our latest rendezvous time.

HELP FOUND

Ken was gone about an hour, and I was starting to again become dehydrated, so I decided that the safest place was back at the creek. I started making my way back. I collected a couple of old brittle refuse plastic water bottles from the side of the road, to use as future canteens. It is best to keep you eyes open, mind sharp and always keep thinking; take advantage of anything you can see or find. As I was laying on the side the road taking a rest, a truck came out of nowhere rumbling up the road around the corner with 2 men - with Ken. He had found a logging crew’s pick up truck which was unmanned, so he walked on to see a pickup truck with two men who then came running up. One of the men had a radio. They radioed to town, so an ambulance was being sent. In the meantime, within 30 minutes, three trucks of first responders arrived. They administered good care of us. The thing I remember most was the large cold orange Gatorade. Thanks guys!

We rode in the back of the pickup truck down the mountain halfway to a main road, 20 or 25 miles, and there we were met by the ambulance, which was slowly making its way up there.

Then we all went down the rest of the mountain in the ambulance on the trail and to the hospital. Staff worked diligently on us all afternoon. Police and Rangers arrived asking questions. Also FAA and NSTB on the phone. Then we were checked out of the hospital. One of the nurses gave us both a ride to check into a hotel nearby.

When in cellphone service range in the ambulance, we both called our wives. They both together flew to Phoenix on the next flight and then drove 4 hours through mountains and canyons of highway in the dark to meet us at the hotel at 12:30AM.

We all drove out late the next morning back to Phoenix, and caught a flight home.

End.

UPDATE ONE WEEK AFTER ACCIDENT:

It has just been reported by the local Indian authorities that it does not appear that there are any more searches going on. They stated further that the area is recently or now closed due to the drought, so there are “not many people allowed in the area”. They expect that once fall arrives, they will reopen the area for hunting and hopefully locate the aircraft. They advised that if the TBM is located, they will notify us right away.

POSTSCRIPT RELATIVE TO MY OBSERVATIONS OF MY BAILING OUT EXPERIENCE:

First, I think it’s critical to have a helmet with an automatic wire disconnect. We had that. Even though I knew it was one of the things to do, I guarantee that in the moment you will not do it. Even though I already knew, and thought about it I had a time, and the dramatic micro seconds, I was not thinking about it. So having “jack disconnects within the overall wire lead” near the helmet was nice. The helmets we had from Campbell Aero Classics had that built-in for that reason. Located about 12” down the line from the ear cup.

When flying over wilderness, I think I was very prepared with what I had stowed (all of my emergency gear was in the life raft tunnel. My food and water was in the radio room - a month’s worth). But the big mistake was not having one thing in my flight suit. In hindsight, I would have prioritized - 1st my sat phone (they are small in size now). combined with my knife, flashlight and a butane lighter, then 2nd - add in a bottle of water. Would have also been nice to have my handheld ELT registered with NOAH.

When you are going through it all, it is obviously imperative to have the parachute already on. We did. Also important is to try to cinch all the straps as tight as possible before you exit. I tried but was unable to effectively get everything cinched like I wanted before I bailed. Was just plain running out of time.

Practice bailing out with a stopwatch with the plane on the ground on occasion at your hanger. I did. Read all the instructional books that you can. Watch all the instructional videos / YouTube beforehand. I did. Make sure everyone flying is beforehand fully briefed. We did. I never parachuted before in my life, and at the end of the day it wasn’t that complicated. All you have to do is stay conscious and pull the big D-ring. But don’t get too anxious. Wait until you clear the plane and you know visually. Then just focus both hands on that D-ring. One hand pulling, the other hand pushing.

I mentioned about the various attitudes of the airplane when I bailed out. Pointing up 20 or 30 degrees, turning, bailing, as I was coming out the nose was starting to go back down on its own. I think this was critical in my not hitting the tail.

Doing it all is rather simple. Unbuckle the seat-belt or 4 point harness, which is one move. Roll out and brace for the tail. I didn’t grab the TBM center bar rail above my head, didn’t seem to need to. That was probably because I was semi weightless from pulling the plane up and then finally letting go of the yoke stick. As you are coming out, I recommend a cannonball position, minimizing your overall footprint to clear the plane. But as mentioned before, the tricky part is getting yourself out after you go into the slipstream and not getting pinned against something like the canopy, or any part of the parachute, flight suit or anything else snagged on anything in the cockpit. I would recommend to do a cockpit check to make sure there are no items projecting out to minimize this risk.

I did not specifically go over the cockpit to check for any projections or items that could cause trouble in this event. However, I was lucky that there was nothing to get in the way. With respect to everything else, I seemed to have executed things correctly and it all worked out.

Hold your breath and count for what will seem like 1 second. Once clear of plane, if high, try to roll onto your stomach facing down belly pulling the D-ring. But that is not essential. I was facing up, had no time to roll over. Not that I would have even known how to do it. As I stated, I have never parachuted before.

That’s it. Once floating down, reach up and try to find the control toggles on the risers so you have directional control and are able to flare at landing.

IMPORTANT - I learned from Strong Enterprises that the reason I couldn’t find the loops was partially because I wasn’t cinched-in tight in the harness, I was drooping down in the slack of the harness after parachute deployment. Also I remember my neck was strained from the deployment in the incorrect position, the shock to my neck and back made it hard for me to move my head back to look up to find the toggles I felt for them, but I didn’t know exactly where they were. Ken has skydiving experience, so he was cinched in his harness tightly, so he found and used them.

Just before coming into the trees, I remember I was amazed how fast I was coming down (based on the fact that I didn’t flare, and the air was much thinner). I bent my knees and tried to be somewhat relaxed when entering the trees. This seemed to help minimize my injuries. The positive is with the additional speed coming in the trees I didn’t get hung up, it did slow the parachute down, but then it all let go and I did a free-fall what I would guess to be 20 feet or so. It’s a coin flip of positives and minuses.

———————————————————————————

I write all this while it is fresh in my mind for the benefit of other pilots to read in the future. I hope this might help someone that might end up in a similar situation.

———————————————————————————

UPDATE - May 15:

NSTB has indicated that the Civil Air Patrol is now intermittently searching for the plane.

CLARIFICATIONS TO MISINFORMATION FLOATING AROUND OUT

THERE:

(1) The .50 caliber machine guns in the wings are FORWARD facing. One in each wing. They were simulated, not real. The gun receivers with ammunition feedways, barrels and barrel jackets were modeled from the real specs, but the internal parts were designed with a complex computerized oxygen and propane mixing firing system. No rounds, no bullets. Only air pressure and noise.

The gun firing to the rear is of the same type, but is mounted in a revolving turret located in the aft position behind the middle seat.

(2) In the news interview, I had indicated that I was “on the instruments”. My reference was to my focus was on the “power indication dials”, mainly special attention being paid to the oil temperature, oil and fuel pressures, and cylinder head temperature gauges. When in more vulnerable positions, most pilots pay double attention to those instruments in order to get as early a warning as possible if there might be any trouble developing. The instruments were all in the green when the engine malfunctioned.

(3) This airplane was re-registered and re-certified in the “LIMITED” category after we took possession in the United States. One of the limitations was no night flights and no IFR, whether the pilot was rated or not. I am a instrument pilot with heavy practical experience in extreme conditions from my expeditions to the high Arctic and other remote places.

(4) The seats are not ejection seats, they are fixed bucket type. Original 1940’s design. The parachutes are vintage configurations, the type you sit on. The seats are set lower and designed to accommodate these parachutes.

PERSONAL REFLECTIONS ONE MONTH AFTER THE ACCIDENT

It was and remains devastating to lose this aircraft. Of course, now after this event, I have gone over and over and over in my mind if there was anything else I could have done to save this ship. After going through all the alternative, now I am sure I did the right things.

This was sudden and catastrophic. We had immediately lost most of our thrust, even before pulling the throttle back to try to bring down the smoke and fire.

It would’ve been suicide to try to land in the trees. Most are 100 to 150 foot high Ponderosa Pines closely spaced on rugged these mountain slopes. I did consider a right base to final to a possible landing spot in a wet marsh / swamp. With my DeHavilland Beaver, I may not have given it a second thought, with those high wings and large floats under me. I had practiced extensively and also had actually successfully executed full engine out landings, once over the smoky mountains to landing strip within range, and once in the wet tundra of the high arctic, both with not a scratch on the plane. But with heavy increasing smoke coming into the cockpit, and knowing that these wings are low, with gear up, there was a good chance of a high speed cart wheel when one of the wings inevitably touches muck first before the other.

I had done my “what if’s” already, way ahead of time before taking my first flight in this airplane. I had played scenarios out - where I would land -and- where I would NOT land, if I ever had a problem. I had already preemptively ruled marshes out.

Putting that all aside, if I had decided to try it in this particular marsh, if I came in short, or came in long, it would have been game-over immediately. There would have been no room for error. And if I may have risked it myself, there was no way that I was not going to risk the life of my friend and crew-mate.

That said, the loss of this airplane is devastating not only for myself, but for the world. We had put so much work and passion into her. There was and still remains a huge connection. She was a flying museum, a marvel to look at. A privilege to fly. I always felt like it was all a privilege, so this is especially tough.

But now reflecting back on what is really important - I am alive. My friend is alive. We are not maimed. We now both get to still see our kids finish growing up, to someday get married, the grandchildren- and all the other great things we all hope for. I’m glad I didn’t gamble all that away.

WHATS NEXT?

This mountain range is closed until early fall because of fire hazard. Until monsoon season, no one is allowed up there anywhere. Hopefully in the fall, the plane is spotted. Presently, no organized aerial or ground searches are underway. More to follow. Stay tuned.

Ongoing new information:

Please help us find this historic treasured airplane.

A $30,000 USD (recently increased from $20,000) reward is active and will be valid up until August 31, 2020. The airplane must be identified with unaltered pictures FROM THE GROUND and then later officially verified by the NSTB that this is our airplane - before reward will be paid out.

Please email any information on the location (first and only to): ifoundtheairplane@gmail.com

Supplementary Instructions to anyone who finds the TBM.

Ongoing new information:

Please help us find this historic treasured airplane.

A $30,000 USD (recently increased from $20,000) reward is active and will be valid up until August 31, 2020. The airplane must be identified with unaltered pictures FROM THE GROUND and then later officially verified by the NSTB that this is our airplane - before reward will be paid out.

Please email any information on the location (first and only to): ifoundtheairplane@gmail.com

Supplementary Instructions to anyone who finds the TBM.

Please follow these guidelines below:

It is most important to note that once the aircraft is discovered AND IDENTIFIED, it immediately becomes the property of the NSTB.

To do this in a proper and coherent way, not to mention in order to collect the reward money, you must notify us FIRST at this email address with the GPS coordinates along with some pictures of the airplane. This is how we will know who found it first. It will be the email timestamp of that determines who founded first.

Hopefully the wreck is still showing the marking of the registration numbers 337. At least enough that would allow us to positively identify it.

We would highly recommend that you also take video, even if it’s just from a cell phone. That, together with the pictures, will help us identify it. Also you cannot share that information with anyone, especially any media. This all needs to go to us, and only through us.

Once we have positvely identified the aircraft, then we will call and notify the National Safety Transportation Board officer contact that is assigned to this case.

Their first move will be sending local law enforcement to go there and secure the area. They will then cordon off and guard the site, and take control of the aircraft.

If the ship is sitting upright, you will not be able to see into the cockpit, it is very high. What I would recommend is carry with you some type of telescopic device that you can connect your iPhone, GoPro or any other camera. Then you would be able to peer into the cockpit without touching anything, and also possibly see into the inside cabin in the lower rear righthand side near the back, if that lower door is open. Do not try to open it if it is closed. The cockpit is an “open cockpit” and the glass canopies were both open, so that should be easy to view.

BUT I caution again, do not touch anything, not even the wings or pieces on the ground, get the images and get out.

______________________________________________________________________________________

______________________________________________________________________________________